The beguiling, mist-covered forest of Los Cedros provides a vision of a future where the rights of the natural world are actively and effectively protected.

By Peter Yeung

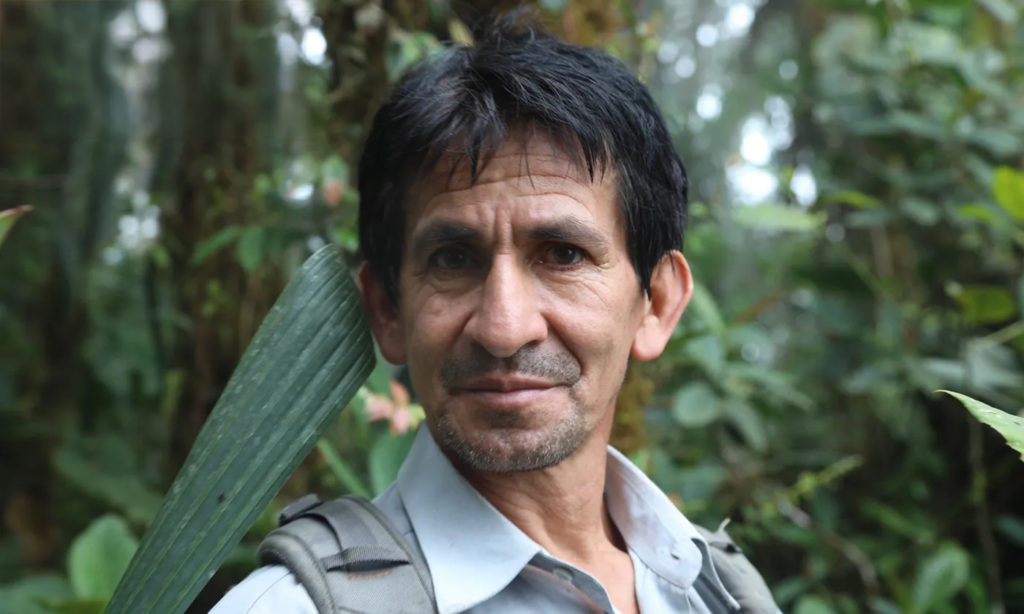

Jose Martín Ovando suddenly halts in his tracks and crouches down along the steep forest path shrouded in mist. He pulls out a magnifying glass from his small backpack to inspect a clump of deep green moss.

Among the greenery, he has spotted an orchid: Dracula morleyi. Blotted in black with a flash of white at the center, it’s barely bigger than a fingernail. “This place is full of so much biodiversity,” he grins. “Scientists don’t even know about most of it.”

Ovando is a guide at Los Cedros Protective Forest, a 4,800-hectare (11,860-acre) cloud forest reserve in the northwest Ecuadorian Andes, one of the world’s most biodiverse areas.

This tropical haven—home to a wealth of wildlife, including the critically endangered black-and-chestnut eagle and brown-headed spider monkey, jaguars, endemic frogs, more than 300 species of birds, 600 kinds of moths, and 200 varieties of orchids—is at the forefront of a global movement to recognize the legal rights of the natural world.

The movement is rooted in the common Indigenous belief that nature—from the Andean mountains to Amazonian rivers to a single soldier ant—is a system to which human beings belong and with which they must harmoniously coexist. The legal theory argues that these ecosystems and species have intrinsic rights that should be protected like those of humans.

“The idea that rocks, rivers, and animals are alive and so should be granted a legal status is a core aspect of Indigenous worldviews,” says César Rodríguez-Garavito, professor of clinical law and director of NYU School of Law’s More Than Human Rights Project (MOTH), an initiative attempting to further nonhuman rights and the larger web of life. “Indigenous peoples have turned that belief into practices of reciprocity with nature, through ceremonies, use of medicinal plants, and more.”

The planet faces a human-led sixth mass extinction that has already wiped out entire species and risks destroying whole ecosystems. This destruction would accelerate under authoritarian regimes and right-wing agendas around the globe, including Project 2025 in the United States. Los Cedros is the world’s leading example of how non-anthropocentric laws can be used to defend the planet effectively.

“By putting ourselves [humans] outside of nature, we’re hurting ourselves,” says Bitty Roy, an ecologist at the University of Oregon who first visited Los Cedros in 1998 and has since returned many times. “We live within the system of nature; we rely on it, and it’s part of us. The rights of nature recognize this in a way that old laws haven’t.”

According to the Eco Jurisprudence Monitor, so-called “rights of nature” arguments, a novel conservation strategy dating back to the 1990s, have been lodged in 397 cases across 34 countries and even the United Nations. These cases have been brought from Bolivia to Brazil to Uganda, as well as Canada, Mexico, and the U.S.

Some cases have broadly recognized the rights of rivers, watersheds, mountains, and even the entirety of Mother Earth. In contrast, others have focused on species like seals in the North Sea, sea turtles in Panama, or a specific animal, such as Tommy the chimpanzee, living in a cage in New York. In one particularly creative case this year, campaigners got music streaming platforms to allow nature to be credited for sounds used in songs.

In Ecuador, the groundwork was set in 2008 when, thanks to lobbying from Indigenous groups, the country adopted a new constitution that included the rights of Pacha Mama, in essence stating that Mother Nature has the same rights as people.

But Los Cedros’ story began much earlier. Today, the reserve is owned by the state, but in 1988, Josef DeCoux, an American environmentalist, purchased the land. DeCoux managed a scientific station at the heart of the reserve until his death in May 2024.

Bit by bit, with the help of friends and nonprofits including Friends of the Earth Sweden and Australia’s Rainforest Information Center, DeCoux bought land in the area to preserve it. For many years, he lived in a shack deep in the forest.

“I fell in love with the unique beauty of the place,” said DeCoux, during a visit to the monitoring station in Los Cedros shortly before his death following a years-long battle with cancer. “I immediately knew I wanted to dedicate my life to this forest. And that’s what I’ve done.”

DeCoux worked with Indigenous communities in the surrounding Manduriacos Valley to build local support for the effort, resulting in Los Cedros securing state conservation status in 1994. “People stopped shooting all the monkeys,” he added.

“They appreciated the reserve, its value, and how it protects the watershed.”

As a result, Los Cedros—which ranges from 3,000 to 9,000 feet in altitude and is crossed by four rivers—thrived, in contrast to the mass deforestation suffered by the surrounding, highly endangered Andean cloud forest. Under an open-door policy aimed at raising the reserve’s profile, scientists came from across the world to study its wealth of biodiversity, with more than 140 scientific papers now published.

“I could spend time studying a single square meter of Los Cedros and still not understand everything there,” Roy says. “Western Ecuador is head and shoulders above the rest of the world in terms of amphibian, bird, and plant biodiversity.”

However, conservation efforts hit a major stumbling block in 2017 when the government granted the state-owned mining company ENAMI EP rights to mining concessions for copper and gold in more than two-thirds of Los Cedros’ landmass.

Here is where the rights of nature legislation came into play. Before extraction could begin, the local government of Cotacachi, a region home to 43 Indigenous communities, tabled a legal challenge at the Provincial Court. After an appeal, the case was then taken to Ecuador’s Constitutional Court. The claimants argued that if mining was to proceed in Los Cedros, it would violate the forest’s constitutional rights, and they demanded the protection of its “right to exist, survive, and regenerate.”

After a years-long legal battle, in December 2021, judges at the Constitutional Court finally annulled the concession granted to the mining company, in effect turning a theoretical constitutional text into a tangible, real-world policy.

The unprecedented verdict was one of the first times that any court in the world had ever recognized the rights of nonhuman organisms—and the judges went as far as to state that the law not only applied to Los Cedros and to other protected areas, but, under the terms of the constitution, to any kind of nature within the country of Ecuador.

“There was no case before this; there was no precedent,” added DeCoux. “It was a case of science winning over extractive industries.”

In Los Cedros, the miners were forced to remove their machinery immediately and the court banned all future mining and other extractive activities.

Now, 24 hours a day, the reserve thrums with activity, from the early-morning roars of howler monkeys among the dense canopy to the afternoon squawks of toucans and the buzzes of nocturnal bats swooping after the many critters that fill the night sky.

“It is a great pleasure to observe the greatness of the animal kingdom here every day,” says Ovando as he watches a pair of yellow-beaked toucans in the distance. “Life is calmer here now. The wildlife is more at ease.”

Follow-up monitoring has also confirmed the early impact of the ruling. As part of a report published by the More Than Human Rights Project in June 2024, Rodríguez-Garavito visited Los Cedros twice and found that mining equipment and staff had been removed from the reserve, which remained a “sanctuary” for biodiversity thanks to the ruling. The report concluded that enforcing the rights of nature and rulings like Los Cedros “can be effective tools to protect endangered ecosystems.”

“I was positively surprised,” Rodríguez-Garavito says. “Especially because Los Cedros is in the midst of the region with many active mining projects. It should not be taken for granted that these rulings will be properly implemented.”

Proponents argue that successfully using those rights to defend an ecosystem like Los Cedros has set a powerful precedent and is already influencing rulings in Ecuador and beyond. In July, the Indigenous Kitu Kara people won a case claiming pollution violated the rights of the Machángara River, which runs through Ecuador’s capital, Quito. In March, Peru recognized the rights of the Marañón River to be free of pollution after a lawsuit was brought by the Kukama Indigenous Women’s organization against the oil company Petroperú. A recent claim relating to Ecuador’s Fierro Urco wetlands even referenced the Los Cedros precedent in court filings.

“It’s a phenomenon that’s catching fire, and that’s spreading very rapidly around the world,” Rodríguez-Garavito says. “Because the Los Cedros case is a sophisticated and detailed judicial decision, it’s being referenced by other courts.”

Nicola Peel, an environmentalist who first visited Los Cedros in 1999 and testified during the Constitutional Court case, argues that the ruling marks a turning point in global conservation. “I absolutely believe that the time has come for the rights of nature,” she says. “This feels like the natural progression for a new era.”

However, plenty of concerns remain over the long-term success of the ruling in Los Cedros, and rights of nature cases more generally, in the face of powerful extractive industries and limited resources to monitor and enforce legal protections.

“The courts move on to new cases,” Rodríguez-Garavito says. “But the argument behind my study is that researchers, policymakers, and advocates must continue paying attention to implementation. We need to follow what happens after.”

The Ganges River, for example, is considered sacred by more than a billion Indians. In 2017, the highest court in the Indian state of Uttarakhand, home to part of the river, recognized it as a “living entity.” However, sewage and industrial waste have continued polluting the river since then, and it remains undrinkable.

Rodríguez-Garavito’s findings also highlighted other threats to Los Cedros: mining activities in nearby areas that risk a “spillover effect,” a growing problem with organized crime in Ecuador that could hinder efforts, “grossly insufficient” resources for park rangers, and the passing of DeCoux, who led the movement.

An ongoing challenge is also maintaining the support of locals, some of whom—in situations of poverty, without alternative sources of income, and barely any support from the state—have been tempted by the pay offered by mining. “Companies always offer them good jobs,” Ovando says.

Others are concerned that the ruling could simply boost illegal hunting, logging, and mining outside the reserve’s borders, resulting in mass biodiversity loss.

“I worry that Los Cedros will become an island surrounded by private lands that get degraded,” Peel says. “How can we ensure the protection of other areas too?”

However, few disagree that the case of Los Cedros, with its beguiling, mist-covered forest, has provided a vision of a future where the natural world’s rights are actively and effectively protected.

“Mining isn’t going to happen here again,” said DeCoux, in a typically direct tone that has driven the conservation success in Los Cedros. “People need to get that into their heads.”

Peter Yeung is an award-winning freelance journalist, covering a broad range of beats, including climate, global health, migration, human rights and cities, often through a critical, solutions-orientated lens.

This story was initially published in Yes Magazine (US) and is republished within the Human Journalism Network program, supported by the ICFJ, International Center for Journalists.