Although there were obstacles along the way, and the far-right now threatens consensus, Spain is a European pioneer in adopting comprehensive legislation or collecting data, and its system is now regularly consulted by other countries.

By Marta Borraz

When it seemed that gender violence did not exist for most of society or that it was a matter of “passionate anger,” Ana Orantes put a face, voice, and words to it. The abuse she suffered at the hands of her husband, this woman born in Granada, in the south of Spain, entered Andalusian homes in 1997 when she told on television the hell she had been living for 40 years. Only 13 days after her television appearance, José Parejo murdered her.

The case was a shock. Over the years, Ana Orantes not only became a symbol but also contributed to the legislative reforms that made Spain a pioneer in the implementation of public policies against gender violence and a benchmark at the European level. This is how the country is conceived from the outside, where the Integral Law against Gender Violence, which celebrates its twentieth anniversary this year, is often highlighted as the jewel in the crown.

François Kempf, a member of the secretariat of the Group of Experts against Violence against Women and Domestic Violence of the Council of Europe (GREVIO), which ensures compliance with the Istanbul Convention by the States, emphasizes: “Spain has been a pioneer in adopting a comprehensive approach to combat gender violence, anchored in the 2004 law”, which has been complemented by a “subsequent evolution of laws and policies that have demonstrated commitment at the highest political level and the will to mobilize society around this objective.”

Although measures such as the regulation of protection orders for victims were approved during the governments of José María Aznar’s Popular Party, it was José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero’s PSOE that promoted the comprehensive framework. Already in 2002, the Socialists had presented in Congress a proposal for a regulation that the recently created Network of Feminist Organizations against Gender Violence had been working on since the 1990s, but the PP voted against it. Finally, on October 8, 2004, the law was approved unanimously.

The law deployed a whole system of protection and care for victims through specialized courts, social and employment assistance, or psychological care, information, and counseling services. But beyond the specifics, the law represented a qualitative leap by recognizing for the first time that gender violence is not something that affects the private sphere but rather a “more brutal symbol of the inequality” between men and women. In its preamble, the law indicates that it is a violence characterized by gender status.

“Although we can be critical, the truth is that comparatively Spain is a reference. A differential element is that here we speak of gender violence as such when in many other states, such as Germany, it is called domestic violence and remains within the family. The name is a very important step forward because it gives a glimpse of the structural reason behind it,” says Noelia Igareda, professor of Philosophy of Law specializing in Gender at the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB).

Before the Istanbul Convention

Data collection is another difference: complaints, sentences, and protection orders are collected in addition to murders of women by their male partners or ex-partners, which have been recorded since 2003 and now exceed 1,200. Teresa Nevado, the former member of the executive committee of the European Women Lobby and now secretary general of the Spanish delegation, believes so: “We began to take specific data at a time when the rest of the countries did not do so, nor did many of them have, nor do they have today, a comprehensive law, which has become something like a model to follow.”

So much so that foreign delegations visiting Spain to learn about the system have become commonplace. Representatives from countries around the world such as France, Argentina, Brazil, Ukraine, Germany, United Kingdom, Egypt, Switzerland, and Turkey have come in recent years to learn about the VioGén System, with which the Police make the risk assessment of the victims and its monitoring, according to the compilation of visits made by the Ministry of the Interior since 2019.

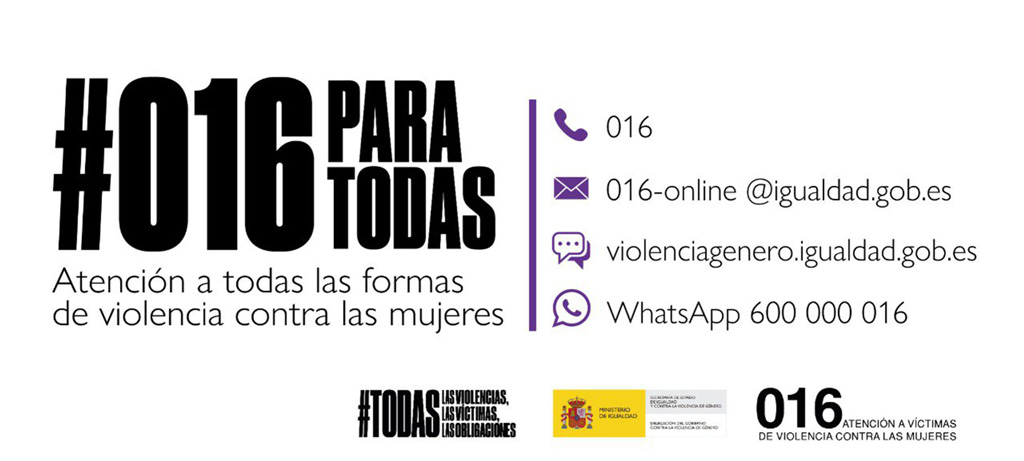

The 0106, a 24-hour, 24/7 hotline for victims or the control bracelets for abusers, are other gears of the system that the visitors are interested in. This “coordinated response” to gender-based violence, which also involves the network of services at the regional and municipal levels, is highlighted by GREVIO, which also focuses on the creation of specialized courts and police units, above all, in the adoption of this comprehensive approach and the recognition of “the gendered nature” of this type of violence “many years before” the Istanbul Convention was adopted, and ratified by Spain in 2014, explains Kempf, who beyond the 2004 law also celebrates the “subsequent development” of laws and policies.

Precisely this lack of gender perspective when investigating crimes against women is something that GREVIO has insistently criticized in numerous countries such as Belgium, France, Malta, Montenegro, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Serbia, according to the evaluation carried out by the group in 2020. Two years later, the country analyzed was Germany, about which, despite progress, the final report warns of “serious shortcomings” and “a general problem” which is the “lack of a national action and coordination plan” on gender-based violence.

Unfinished business

The Spanish journey, however, has not been without obstacles. The comprehensive law of 2004 was the subject of numerous legal appeals arguing that the law discriminates against men, a discourse that continues to be accepted by part of society and the political sphere, even though the Constitutional Court ruled in favor of the law in 2008. But beyond the resistance, there are still many gaps in the protection and support of victims of gender-based violence that have yet to be filled, according to the experts.

“There are countries, such as the Scandinavian countries, which have very strong and powerful welfare states and perhaps there in the field of social services, the community network of support or social benefits are more developed,” says Igareda, and says that, for example, “it is one of the countries similar to Spain in terms of legal definitions.”

In its latest evaluation, GREVIO pointed to the “deficiencies” in Spain to guarantee “the safety of women and children” victims of gender violence when deciding custody or visitation regimes, something that has also been recently highlighted by the UN, which has pointed to the Spanish judicial system for failing to protect minors from “abusive fathers.” But what most concerns the group of experts is that the system does not cover other forms of male violence beyond that of the partner or ex-partner, for example, in terms of support services or psychological care.

On the other hand, for Igareda, “the great unfinished business in Spain” is for the public policy designed on paper “to be deployed in its entirety.” “The letter is advanced, but resources, training in gender perspective, accompaniment of victims and minors, and reparation must accompany it. They must be heard, listened to, and believed, something that is not happening today,” she says.

The threat of denialism

However, GREVIO will evaluate Spain again this year, specifically on the issue of “building trust by providing support, protection, and justice to victims.” It will also evaluate the measures that have been taken in recent years, in which the Ministry of Equality has promoted the “Solo sí es sí” (only yes is yes) law, which creates a comprehensive framework of care for victims of sexual violence. In addition, care services such as 016 have been extended to other forms of male violence, all femicides have begun to be officially counted and the use of false parental alienation syndrome (known as SAP for its acronym) has been vetoed.

In 2021, the renewal of the State Pact against Gender Violence was promoted, a great agreement of parties supported by all but Vox. The far-right, which denies gender violence and calls for the repeal of the Integral Law, has emerged with force and entered the governments of autonomous communities and city councils.

Although we will have to wait to see how this crystallizes in practice, what the experts do believe is that it is a palpable threat: “To the extent that the far-right can decide on public spending in communities and municipalities, they can decide not to invest or to invest less in the network of assistance, shelter, and public services. They are denying the existence of gender violence, which has an impact.”

This story was originally published in elDiario.es (Spain) and is republished as part of the Human Journalism Network program, supported by the ICFJ, International Center for Journalists.