Northern Nigeria has a history of vaccine hesitancy, affecting millions annually. With cash incentives, an organization achieved over 3 million doses.

By Ogar Monday

Gombe, Nigeria: It’s 8 AM on Monday, August 26, 2024, at the Pantami Primary Healthcare Centre in Pantami, a suburb in northeast Nigeria’s Gombe State. The children’s vaccination hall is filled with a vibrant array of hijab colors—green, brown, white, and more, representing a mix of young and older mothers who brought their babies and toddlers for vaccination.

Among them is 37-year-old Ashaitu Adamu, a mother of three. Inside the hall, a healthcare worker dressed in gray scrubs calls a number, and Ashaitu steps forward with her 15-month-old toddler, Fatima. The worker collects Fatima’s vaccination card, verifies it against the center’s records, and directs Ashaitu to another hall section.

There, Fatima receives her final dose of the MCV vaccine, which helps prevent the virus that causes measles in children. The World Health Organization describes measles as an airborne disease that is “highly contagious.”

But this last dose, which is also the last of the various vaccines she had been scheduled to take, means more than just disease prevention; it is also a hunger reliever for Ashaitu’s family. The dose makes Ashaitu eligible for N5,000 ($3) livelihood support.

“My husband has not received his salary, and I left the house after morning prayers. My husband will come back to see food in the house today, all thanks to this money,” she says.

By 10 AM, the room still has at least 50 women with their children waiting for vaccinations.

“It hasn’t always been like this,” says Khalid Dauda Boi, the facility’s routine immunization officer, implying that mothers scarcely brought their children for vaccination until a cash incentive was introduced. “We often had to go out and persuade women to bring their children for vaccinations.”

The change from vaccine apathy among mothers to ensuring their kids are fully immunized is thanks to an initiative that rewards caregivers like Ashaitu in several northern Nigerian states for consistently ensuring full immunization of their children.

This cash support is a program of New Incentives or NI. This US-based nonprofit, founded in 2011, believes that poor families’ lack of money means they prioritize daily survival, leaving little attention to activities that improve family health or educational outcomes. It refers to its cash incentives as conditional cash transfers.

“A conditional cash transfer is a small amount of money given to somebody in need after they participate in certain activities, and that could be…preventative healthcare,” said its founder, Svetha Janumpalli.

In Nigeria, NI conducts its activities as All Babies Are Equal Initiative, a local organization founded in 2014. It works to drive child vaccination in poor communities across nine northern Nigerian states.

The North and vaccine hesitancy

Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, grapples with a high burden of vaccine-preventable diseases, including meningitis, polio, and measles. A 2019 study by Gavi Zero Dose Learning Hub estimates that at least 41% of deaths among children under five in Nigeria may be vaccine-preventable.

But vaccine distrust, especially in the Muslim-dominated north, is a major obstacle to disease prevention. The hesitation is understandable, and it stems from Pfizer’s 1996 failed meningitis vaccine trial that left 11 children dead and more with permanent disabilities.

In 2003, Muslim leaders in Kano State led a 15-month boycott of the polio vaccine. The result was a 30% surge in confirmed polio incidents in the country amid a national effort to attain a polio-free status.

Insecurity in the region has also slowed down the immunization rate. For example, nine immunization workers were shot dead in Kano by gunmen suspected to be members of Boko Haram insurgents.

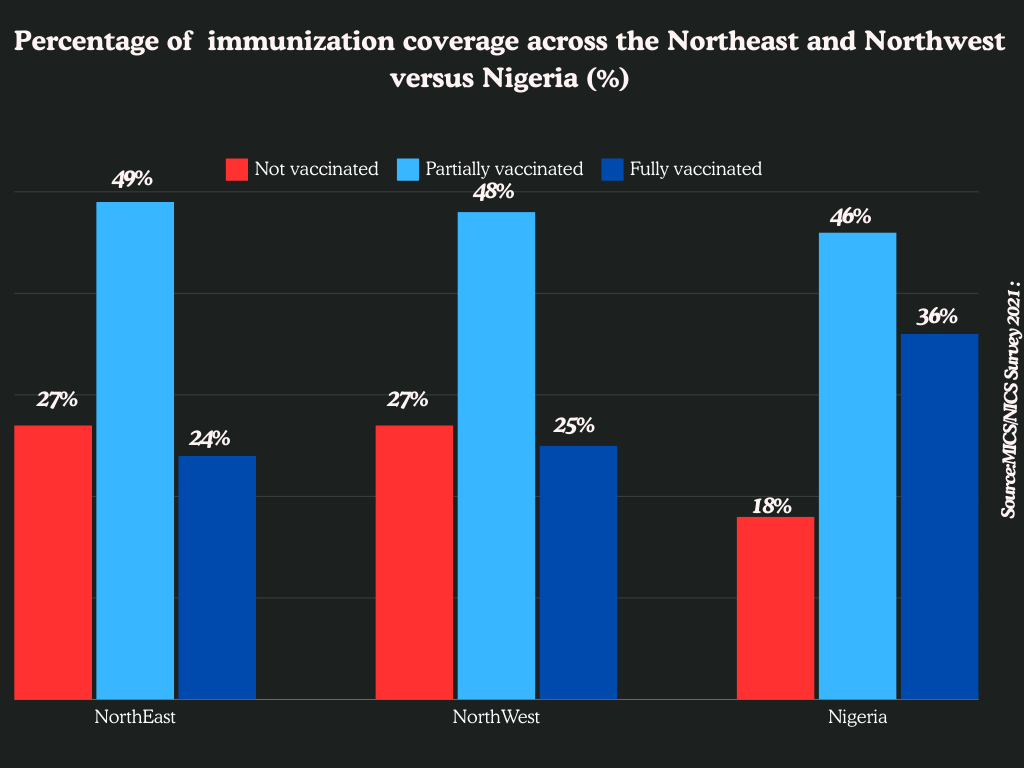

According to figures from the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey/National Immunization Coverage Survey, the northwest and northeast (where Gombe State is) recorded the highest numbers of unvaccinated children by 2021. The northeast, in particular, had a 27% zero-dose vaccination rate and a 49% partial vaccination rate—the highest in the country. Overall, the region had just 24% vaccination coverage, falling short of the national average of 36%.

The little cash that means much

New Incentives provides a N1000 (USD 0.60) cash incentive to eligible caregivers (parents) each time their child takes a vaccine dose as scheduled. “That encourages them to come to the facility for immunization,” said Abdurrahman Shaibu, executive director of the Gombe State Primary Health Care Development Agency.

After the final dose of the last vaccine, a caregiver receives ₦1000 and an additional ₦5000 (USD 3) for adhering to the vaccination schedule until the end.

For many women in poor communities, the absence of such incentives means they cannot afford transportation to vaccination centers, which can be a major reason for missing schedules for their babies and toddlers.

In the last decade, a cost of living crisis set off by heightened inflation has driven Nigeria’s poverty rate to a staggering 40.1%. More than 40 million women—mainly in the northern region—live in extreme poverty. Last year, the cost of transportation in the region rose by over 90%.

“Sometimes, I wake up with no money,” said Patience Joy, a caregiver, emphasizing how she would have missed vaccination appointments if NI was not supporting her transportation costs.

Partnership-driven

Nine of the 19 northern states NI operates in are Bauchi, Gombe, Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Kebbi, Sokoto, and Zamfara. Intervention in a new state begins with a rapid assessment, which is a “baseline survey to understand the vaccination coverage level in that area,” said Mustapha Kabir, operations coordinator for northwest and northeast.

After six months of operating in such locations, “We try to collect data to assess the level of improvement,” Kabir added.

The organization relies heavily on partnerships with local state authorities, such as the Gombe State Primary Health Care Development Agency. It also works with local chiefs and religious leaders, who wield significant powers in rural communities, to raise awareness about the benefits of vaccination.

NI clarifies that it does not provide vaccines but works to identify and address barriers to vaccination and non-compliance cases.

“Government agencies and immunization partners procure vaccines and play all active roles in the supply chain. Our role involves coordination and communication to identify and resolve supply issues and bottlenecks. All of this supportive work is carried out with our government partners at the local, state, zonal, and national levels,” it says on its website. But “We also aim to improve the quality of local healthcare facilities by ensuring proper documentation and that clinics are active and serving the required caregivers,” adds Kabir.

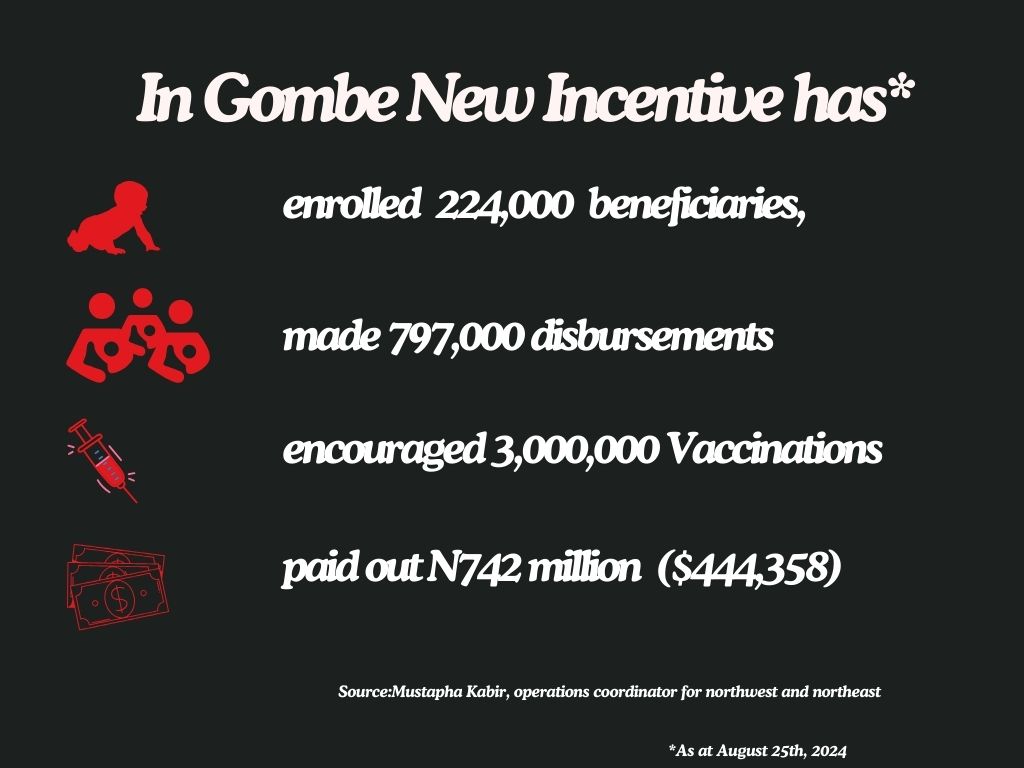

He said that in Gombe alone, NI has enrolled about 224,000 beneficiaries, made 797,000 disbursements amounting to about N742 million (about USD 444,358), and encouraged over three million vaccinations.

Shaibu, the director of the Gombe State Primary Health Care Development Agency, said his office uses harmonized data, community surveys, and feedback from community healthcare facilities to measure the impact of NI’s program. “The result shows a significant increase in demand for immunization across our primary healthcare facilities,” he admitted.

The secretary at the Pantami Primary Healthcare Center in Pantami, Ahmed Mohamed Bello, agreed. “The number of caregivers over the last two years has more than doubled,” he said. “Without the new incentives, we might have only seen a third of the usual turnout.”

A new problem

The influx of mothers into health centers seeking vaccination has created a new problem for the centers: A shortage of healthcare workers to effectively meet the demands. And despite efforts to fight vaccine distrust, some husbands still remember the failed Pfizer incident and continue to prevent their wives and children from receiving the vaccine.

But those who have been receptive say they have evidence that the vaccines have been helpful.

“I now know the benefit of the vaccination. My children don’t have these common childhood illnesses,” Ashaitu said.

This story was initially published in Primer Progress (Nigeria) and is republished within the Human Journalism Network program, supported by the ICFJ, International Center for Journalists.