How a British Columbia Indigenous community is reintroducing traditional fire knowledge and practices to manage land vulnerable to wildfires

Text by Wendy Stueck – Photography by Jesse Winter

The setting was idyllic: a clearing of tawny grass, ringed by ponderosa pines under a robin’s egg sky. Trucks pulled up, coffee and doughnuts appeared on a tailgate and a dog lolled in the sun.

Within a couple of hours, some of those trees were on fire. Smoke was billowing into the sky, and the trucks were scattered, their crews were dispatched to various locations to control the blaze.

But they weren’t extinguishing it. They were continuing to light it, using drip torches to send lines of fire rippling through dry grass, turning tall trees into giant candelabras, and keeping a close eye on boundary lines the flames were not supposed to cross.

The exercise carried out over two days in late April on the ʔaq’am First Nation near Cranbrook, British Columbia, was a prescribed burn: a fire set intentionally to meet specific objectives, such as reducing wildfire risk.

Just as a homeowner might guard against wildfire by clearing brush from around their home, a prescribed burn clears out low-lying branches and dead shrubs, leaving less fuel if a wildfire comes through.

As wildfire seasons become longer and more intense, experts say prescribed burns can help prevent forests from becoming out-of-control infernos. For Indigenous peoples, the revitalization of traditional fire knowledge and practices is emerging as an important strategy for adapting to wildfire threats.

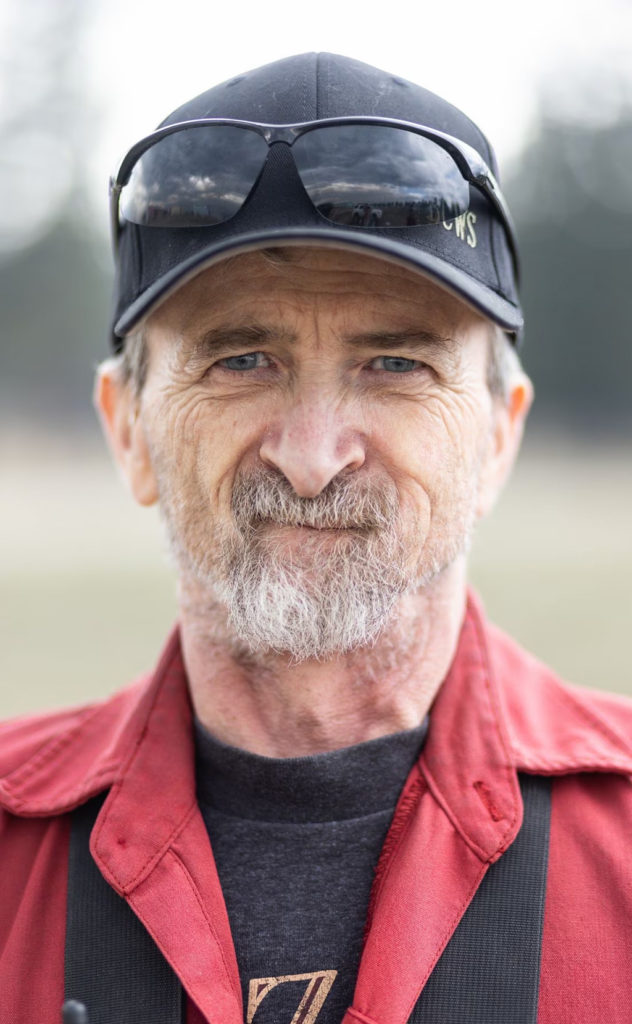

“We’re going to get a lot more big, ugly fires unless we do more prescribed burns,” said Robert Gray, a B.C.-based wildfire ecologist who helped plan the ʔaq’am burn.

And in some cases, like this one, a prescribed burn requires cooperation between groups that have not typically worked together and, in fact, may once have been at odds over when and how fire should be used.

ʔaq’am is a member community of the Ktunaxa Nation, an Indigenous people whose traditional territory lies in the Kootenay region of southeastern British Columbia and who historically used fire to manage the landscape.

When ʔaq’am elder Marty Williams opened the day’s event with a prayer, he began by telling the assembled crowd that although the planning for the prescribed burn had taken place over the previous five years, the community had been talking about re-introducing fire to its land management regime for decades. (The term “prescribed” fire is sometimes used interchangeably with “cultural” or “traditional” burning, which refers to Indigenous use of fire to manage resources by, say, improving conditions for berries to grow or wildlife to graze.)

“This is a fire-driven ecosystem,” Mr. Williams said. During his lifetime, he said, he’d seen elk and deer displaced from the area by logging, agriculture, and unhealthy, overgrown forests, although the animals are now making a comeback. He expects they’ll get a further boost from the prescribed burn, which covered 1,200 hectares, or 12 square kilometers.

“That’s what success looks like,” Mr. Williams added, “when you’re able to come out here and see all the elk and the deer.”

Since prescribed burns can be undertaken by various authorities, including municipal, provincial, and First Nation governments, it’s difficult to track the practice at a national level. However, a 2022 paper in Environmental Research Letters that tracked prescribed burns in British Columbia from 1970 to 2021 found the area burned declined significantly between the 1980s and the early 2000s and had barely budged since. (The estimates did not include cultural burns over that period.)

There are signs that the trend is shifting. Parks Canada has been using fire as a management tool since the mid-1980s, based on the growing recognition that many park ecosystems are “fire-adapted,” meaning fires can improve forest health and biodiversity. Lodgepole pines have resin-sealed cones that can stay on the tree for many years and pop open during a fire, resulting in a new stand of trees. After a fire, woodpeckers swoop in to feast on bark beetles and other insects that colonize burned trees. Moose and elk chomp on new shoots that spring up from black earth.

Wildfire experts like Mr. Gray say prescribed burns can help prevent wildfires by reducing fuel that’s built up over decades. And with climate change expected to dry fuel and make wildfires more intense, such preventive measures could become critical.

About 2.5 million hectares of forest burns in wildfires each year in Canada, a total projected to double by 2050. Canada already spends about $1 billion a year fighting wildfires, according to federal figures, but the damage from evacuations, industry shutdowns and destroyed homes and businesses can be much greater. Costs related to the 2016 Fort McMurray wildfire, for example, have been pegged at about $9 billion.

Wildfires larger than 100,000 hectares are becoming “commonplace” in western Canada, researchers said in a 2022 paper in the journal Environmental Research Letters. That’s holding true in the Canadian province of Alberta this year, where, as of May 27, Alberta Wildfire listed nine wildfires of note, including the Long Lake fire, described as “out of control” at over 124,000 hectares.

Those fires are expected to have an oversized impact on Indigenous people. A 2022 report by Canada’s Auditor General Karen Hogan found disasters such as floods, wildfires and landslides are happening more often, with greater intensity, and disproportionately affect First Nations people because of the relative remoteness of their communities as well as their socio-economic circumstances. Ms. Hogan criticized Indigenous Services Canada for being reactive instead of preventive, noting the department over the preceding four years spent 3.5 times more on responding to emergencies than on supporting First Nations communities to prepare for them.

Those factors help explain why the ʔaq’am burn felt so momentous.

It was also momentous because of the teamwork required. The burn involved personnel from ʔaq’am, the British Columbia Wildfire Service, fire departments from Cranbrook and Kimberley, and contractors – about 75 people in all.

That level of cooperation is significant, given the history of tension and legal barriers when it comes to who can burn what land, and under what conditions.

In Canada, First Nations retain the right to undertake cultural burning on reserve lands, but “significant wildfire agency oversight and control is often required, leading to tensions when cultural burning goes ahead with no formal government approval,” said a 2022 study on Indigenous-led fire stewardship in Canada.

The British Columbia Wildfire Service has penciled in about 65 cultural and prescribed burns this year that, together, would amount to about 10,500 hectares if conditions allow them to go ahead. About half of those projects are expected to have burn plans developed by or with First Nations, the agency says.

That marks a shift from past practices. British Columbia was the first province in Canada to ban cultural burns, through the Bush Fire Act of 1874, and other jurisdictions followed. Wildfire legislation has since been updated and policies and practices are evolving. Its local wildfire service, the BCWS, , for example, says it is committed to reconciliation and is partnering with Indigenous communities on multiple projects, including cultural burns.

But BCWS lags behind Australia and the United States in embracing the practice, Mr. Gray points out, citing New Jersey as an example. In February, the state announced plans for about 10,000 hectares of prescribed burns this year – roughly the same area slated for prescribed burns this year in British Columbia, which is about 40 times as big as New Jersey.

On the ʔaq’am fire, the cooperation showed. Radios crackled with messages between personnel tasked with starting, directing, and controlling the flames. Burn boss Colleen Ross, who co-wrote the ʔaq’am First Nation burn plan with Mr. Gray, steered the operation, taking into account factors such as wind, temperature, relative humidity, and visibility for the nearby Canadian Rockies International Airport.

As crews used drip torches on the ground, a BCWS aerial ignition team crisscrossed overhead in a helicopter equipped with a plastic sphere dispenser, a device that shoots out what looks like ping-pong balls. Once they hit the ground, the spheres undergo a chemical reaction and ignite, giving crews another tool to control the direction and spread of the burn.

Over four decades with BCWS, ignition specialist Mike Morrow has seen aircraft become faster and more agile, and the systems used to detect and track wildfires grow more sophisticated. But as quickly as technology evolves, fires seem to leapfrog past it.

“The technology has increased, but the fires have changed,” Mr. Morrow said, adding that today’s conditions reflect decades of fire-fighting policies that focused on fire suppression and prevention, allowing fuels to build up to dangerous levels.

“And by doing this, we can punch holes – so it can get up and be a raging fire, but when it runs out of fuel, it comes down.”

In addition to prescribed burns, Mr. Gray, the ecologist, would like to see more attention – and money – directed toward measures intended to limit wildfires, such as thinning and pruning bush.

The two-day ʔaq’am operation cost about $250,000, while total costs for the project ―including planning, supplies, and equipment― amounted to about $1.6 million, says Michelle Shortridge, information officer for the band.

That included work over the past few seasons to thin and harvest some timber from the site to make for a safer burn. Not all the site was treated, but that was a tradeoff, Mr. Gray explained: it could have taken a year or longer to cobble together grants to treat the whole site, during which time the risk of a serious wildfire would have increased.

Tradeoffs and risks are a constant when it comes to prescribed burns.

Last year, the U.S. Forest Service put a temporary hold on the practice after a prescribed burn in New Mexico escaped, turning into a massive fire that caused significant damage. A U.S. Forest Service Review, released in September 2022, made seven recommendations to strengthen prescribed burn procedures but also affirmed the importance of the practice, saying the agency ignites about 4,500 prescribed fires each year and almost all ―99.84 percent― go according to plan.

On May 3, a Parks Canada burn, Compound Meadows in Banff National Park, flared out of control due to an unexpected shift in wind direction. About three hectares burned outside the prescribed boundary, forcing some area businesses to evacuate. By May 6, the fire was classified as “under control” and Parks Canada said it is reviewing the incident.

As of May, Parks Canada had two dozen planned prescribed fires listed for possible completion in 2023. They ranged from a five-to-10-hectare community fireguard near Jasper to a 3,300-hectare project, Porcupine Valley, in Yoho National Park, meant to improve habitat for species at risk, like grizzly bears, and reduce wildfire risk.

There’s hope that projects like the ʔaq’am fire can light a path forward, especially by connecting multiple agencies and their respective crews.

“For me, it’s about being good neighbors, being good partners, working together,” Ms. Shortridge said. “And not only on these projects but when we have to deal with emergencies. It makes it so much less stressful and so much easier when we all know each other and that we can work together.”

This story was originally published in The Globe and Mail (Canada) and is republished within the Human Journalism Network program, supported by the ICFJ, International Center for Journalists.