Hundreds of thousands of Rohingya, a Muslim community, had to leave Burma due to persecution. They settled in refugee camps in countries like Bangladesh and India. In New Delhi, the women’s work in coordination with humanitarian aid agencies is helping increase the schooling of Rohingya girls, combating child marriage and improving health conditions.

By David Flier

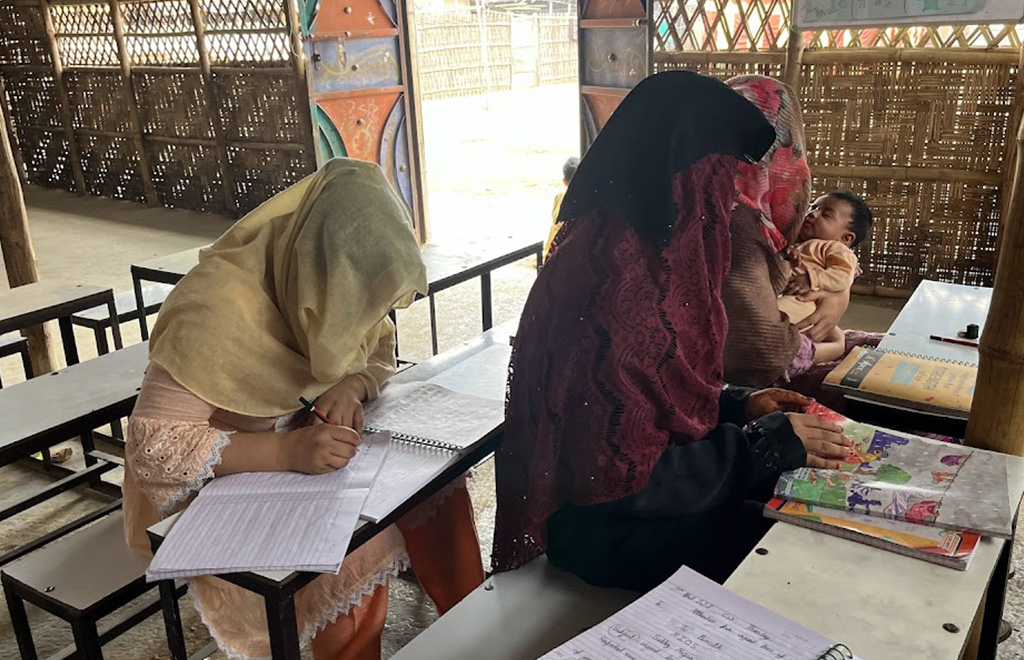

“When a girl turns 13 or 14, her family stops sending her to school and lets her do household chores,” says Minara, 30. She was born in the town of Buthidaung in Burma’s Rakhine State. She is a widow with four children and has lived in India since 2012. She is one of three Rohingya community leaders elected by the inhabitants of the Kalindi Kunj refugee camp in New Delhi, India. Her work is aimed at tackling a specific problem: the lack of schooling, which in turn creates challenges for the social inclusion of her community.

The Rohingya are an ethnic group, mostly made up of Muslims, who, according to the United Nations (UN), are the most persecuted minority on the planet. They are people who have inhabited Burma, especially the state of Rakhine, for centuries but are not recognized by the Burmese government, whose constitution denies them citizenship and has deprived them of rights for decades.

The persecution of the Rohingya became more widely known after a Burmese army operation in August 2017 killed 25,000 Rohingya people and forced the displacement of more than 700,000 Rohingya people to other nations (mainly Bangladesh) as refugees.

There are an estimated 40,000 Rohingya in India, mainly in cities such as Jammu, Hyderabad, Nuh, and New Delhi. Despite the fact that their rights were not recognized in Burma and that they were victims of persecution and violence, life for the Rohingyas has not been easy in other countries. In India, they have difficulty accessing jobs and documentation, and the vast majority live in precarious refugee camps. They are also often victims of discrimination. In these settlements, conditions are far from ideal, with little access to health care and much insecurity. Many Rohingya have been deported back to Burma.

It is hard to tell for sure how many Rohingya refugees live in India. “Many are evicted from the camps, and fires are very often reported there,” says Geetanjali Krishna, a New Delhi-based journalist who covers activities in Rohingya refugee camps. There are suspicions that some of these fires may have been intentionally set.

Local women leaders

Different organizations work on the ground to help social inclusion and the promotion of human rights among Rohingya refugees, such as UNHCR, the UN refugee agency, or ROHRIngy, an NGO operating in New Delhi. Minara’s case reflects how when these organizations work with women community leaders, and they are the ones driving change, results are achieved. “Each camp has leaders who pursue their own independent agenda. But aid agencies organize workshops where these leaders can be trained to help their community,” explains Geetanjali.

Kalindi Kunj is home to 240 people and 14 school-age children over the age of 12. All of them started attending school thanks to Minara’s awareness-raising work.

This is a huge cultural change for a patriarchal community where women are often relegated. “When families understood that women can study and work, it was an ‘eye-opener’,” says Minara. She explains it takes a lot of work to convince families how important it is for women’s future that they attend school.

Minara also raises awareness among families about the dangers of underage child marriage, a practice still entrenched in her community. As a result of her work, there have been no recorded marriages of underage girls in the camp in the past five years.

She sees the presence of community leaders as key to addressing urgent problems. “Agencies and NGOs give us training to share knowledge with the community, but if an incident happens, they or authorities like the police are slow to arrive,” she says. She stresses how important it has been for the community to have created a camp security committee (made up of her and other women and men from the camp), which is in charge of going around the camp every night. There have been two major fires there, in 2018 and 2022, which led to the establishment of this committee.

“There is a greater sense of security since people patrol the streets of the camp at night. Before, residents were worried that part of the camp would burn down at night,” says Geetanjali.

“For all my life I have seen humanitarian aid projects in refugee camps that are good, but mainly designed and implemented by foreigners. That’s why many of them don’t succeed,” says Mizan. She is 21 and in the 10th grade of school in India. She lives in Kalind Kunj and migrated to India in 2014.

During the pandemic, as she motivated other girls in the camp to attend online classes, she also sought to raise awareness among families about the importance of schooling and processing documents to access rights. She expects to become a social worker once she finishes school. “Who can understand the problems of refugees better than refugees themselves? Why can’t we be our own leaders?”, she asks in one of the editions of the Rohingya Stories newsletter, written by Geetanjali.

“In some areas, agencies providing assistance are very helpful, for example, to explain local laws. But it is definitely a problem when people come to help from outside without understanding our conditions or our problems,” says Minara. She adds that as a community leader, she enjoys working cooperatively with agencies.

In the newsletter Rohingya Stories, the author lists some of the benefits she felt when inclusion and human rights projects were led by the refugee community itself. Refugee women leaders, she says:

- They identify the painful aspects of their community more effectively.

- They are good at building bridges between agencies and their community.

- They develop effective and culturally appropriate solutions for their communities.

- They tell the stories in their own words.

The role of women

Hafsa lives in another camp in New Delhi, called Shaheen Bagh. She is 22 years old and has three children. Based on UNHCR training, she goes around the camp and advises the women in each family about their health care, the importance of keeping up with children’s immunization schedules, leaving shame behind and consulting doctors. Sometimes, because she speaks fluent Hindi (the most popular language in this part of India), she accompanies women patients for routine check-ups and acts as a translator.

For her part, Minara feels that her understanding of women’s and children’s problems is greater than that of men. That is why her work as a domestic conflict mediator in her community is important.

“Women bring an additional benefit: wherever they take the lead, progress is made,” says Geetanjali. Before I met Minara, I met male community leaders, and they had a different sense of community. Rohingya women are among the most oppressed, they have very little access to education and job opportunities, so it is important for them to lead their community. They can fight for their agenda better than any men.

The Indian journalist also points out that the task of women community leaders “comes at a great personal cost,” because, while they try to raise awareness of their rights, they live in a community that is still male-dominated. And she points out another detail: because of their Islamic roots, Rohingya women are more willing to talk to other women than to men.

India is not the only place where women play a significant role within refugee communities. In fact, in Bangladesh, the Asian country where most of the Rohingyas have migrated, the importance of female community leaders has been extensively studied.

For example, a 2019 report by the International Organization for Migration lists 10 points that Rohingya men value in the role of women. Among them, they note that “they have good leadership skills and the ability to handle different demands of the community”.

Also in 2019, the Women’s Refugee Commission (WRC) published a study in which it notes that promoting female leadership among Rohingya refugee communities in Bangladesh “provides promising models for transformative change.”

This story was originally published on RED/ACCIÓN and is republished within the Human Journalism Network program, supported by the ICFJ, International Center for Journalists.